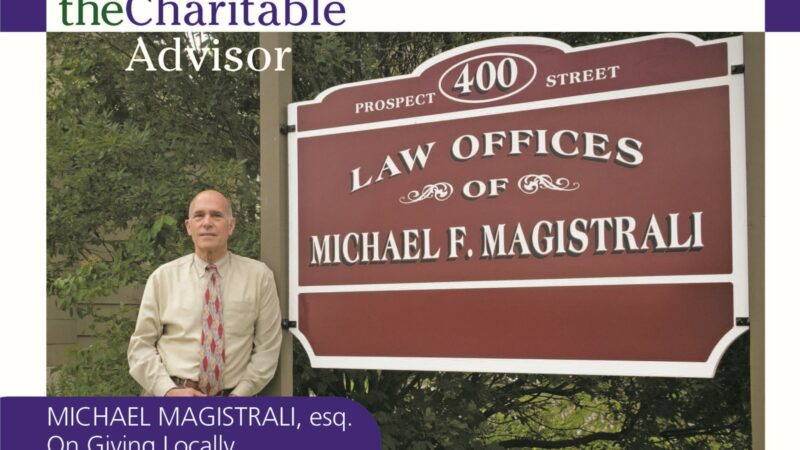

An Interview with Attorney Michael F. Magistrali, esq.

The Community Foundation recently sat down with Michael Magistrali, esq. of Michael F. Magistrali & Associates to discuss giving locally and simple planned giving options.

An Interview With Attorney Michael F. Magistrali, Esq.

The Community Foundation recently sat down with Michael Magistrali, esq. of Michael F. Magistrali & Associates to discuss giving locally and simple planned giving options.

NCCF: How do you advise clients who want to give back to their communities?

MM: Most people who want to leave a bequest have given to different charities throughout their lifetime, and they want to continue that giving through their will. Others really haven’t given much in the past, but have accumulated some wealth and want to do something helpful through their estate planning. Most of my clients are local people who want to support local nonprofits.

The charitable giving conversation comes up most of the time—not all of the time—with clients who don’t have any children or living siblings. If a client seems unsure about what they want to do with their estate, I sometimes ask, “Have you thought about charitable giving?” Many people have specific charities in mind. Others have a general interest, such as food insecurity, childcare, homelessness, or animal-care issues.

Clients often think in terms of a fixed gift amount. If it’s important to them to ensure that all of the nonprofits they care about receive a gift, I suggest they think in terms of percentages of their residual estate. For instance, if you give $50,000 to Nonprofit A and divide the remainder of the estate among Nonprofits B, C, and D, and the day you pass away, you have $50,000 total, Nonprofits B, C, and D will not receive anything. But, if you break your gift up into percentages, each nonprofit will get something. It’s important to think about the consequences of how you frame your bequest.

NCCF: What are some misconceptions about planned giving?

MM: You don’t have to have millions of dollars to give charitably. Most of my clients are not high-wealth individuals. It’s rare for me to have a client who has more than $500,000 in their estate planning. Many have less, but even a small percentage of a small estate can be a very nice gift to a nonprofit.

Another misconception is that you need to be very specific about how a gift can be used. Clients sometimes have the idea that they should restrict their gift to a specific program or item, in essence dictating how the nonprofit can use the gift. I advise clients that they may be unintentionally making things difficult for the nonprofits they want to help.

Most nonprofits want gifts to be unrestricted, so they can use them where they have the need. Nonprofits often have specific bequest language available for use in wills. When the nonprofit receiving the bequest provides the bequest language it ensures that the gift will provide the greatest benefit.

NCCF: You have mentioned that you advise your clients to keep their giving simple. Tell us more about that.

MM: I try to simplify things for clients. Sometimes clients have elaborate plans for their estates. They may want an inheritance to be held in trust and then awarded to recipients at specific ages, or tied to a series of accomplishments on the part of the recipients. Complicated wills, whether they be for inheritances, charitable giving, or both, are very difficult to administer. They take a lot of time, a lot of energy, and clients are not high-wealth individuals, I don’t create charitable lead or charitable remainder trusts. In many cases, charitable giving can be as simple as designating a nonprofit as the beneficiary of a life insurance policy.

NCCF: When do you recommend your clients give through the Northwest Connecticut Community Foundation?

MM: I have been recommending clients give through the Northwest Connecticut Community Foundation since its inception in 1969. When I have a client who wants to make a charitable bequest, but has broad interests or isn’t sure where they want their gift to go or for what cause, I always refer them to the Northwest Connecticut Community Foundation.

Community Foundation staff are able to provide language for wills that ensures the bequest will be used as my client intends. Whether a client wants to support specific causes, establish a fund in a family member’s name or support local nonprofits when and where they need it the most, I recommend the Community Foundation.

Charitable Lead Trusts in a Low Interest Rate Environment

Charitable lead trusts are a creative estate, income and charitable tax-planning strategy for high-net-worth individuals. Lead trusts often involve significant legal and administrative costs and are more complex in nature than other charitable vehicles. However, with historically low applicable federal rates (AFRs), charitable lead trusts have become more attractive as a planning tool.

A charitable lead trust (CLT) is an irrevocable charitable trust where the annuity or unitrust payouts are made at least annually to a selected charity or charities. Reg. 20.2055-2(e)(2)(vi). Because the charity receives the interest first, it has the “lead” interest. After the lead interest terminates, the trust corpus will return to the grantor of the trust or to beneficiaries selected by the grantor, usually family members. If the lead trust is qualified and makes an annuity or unitrust payment to charity, the donor will qualify for a gift, estate or income tax charitable deduction equal to the present value of the income stream to charity. Reg. 25.2522(c)-3(c)(2).

While many charitable trusts are tax exempt, lead trusts are not. The taxation of the lead trust and the benefits to the donor will depend on the drafting of the lead trust. It is the structure that creates unique income, estate or gift planning opportunities for the grantor of the trust. This article is Part I in a two-part series. This article will discuss the structure and taxation of the three different types of lead trusts: grantor lead trusts, non-grantor lead trusts and intentionally defective grantor lead trusts. Part II will discuss the unique planning opportunities currently available with CLTs with a focus on the historically low applicable federal rates (AFR).

Grantor Lead Trust

The goal of a grantor lead trust is to generate a current income tax deduction. The grantor of a grantor trust retains certain powers over the trust. With a grantor lead trust, the remainder of the trust corpus reverts to the grantor or to the grantor’s estate at the end of the trust term. These powers make the trust includable in the current assets or the estate of the grantor. If a lead trust is created with a reversion of trust assets that exceed 5% of value to the grantor, the lead trust will be deemed a grantor trust. Sec. 673(a). The grantor trust is subject to the grantor trust rules of Sec. 671-678.

The primary benefit of the grantor lead trust is an income tax charitable deduction. With a grantor lead trust, the donor (or grantor) will receive an up-front income tax deduction for the present value of the income that is projected to be paid to charity. Sec. 170(f)(2). The donor must pay all taxes during the term of the trust for any taxable events that occur within the trust. The donor will recognize all income and capital gain on the donor’s Form 1040. The income distributed to charity will be reported in the donor’s personal adjusted gross income. This means for each year of the duration of the trust, the donor will be responsible for the tax implications of the trust. Sec.170(f)(2)(B).

The assets in the trust are usually invested in such a way as to minimize recognition of income (such as income that occurs on the payment of stock dividends or the sale of highly appreciated capital assets). Because the donor is personally paying these taxes during life, the trust corpus is preserved from tax depletion. Note that if a grantor passes away during the trust term, there is a recapture of part or all of the income tax deduction, because the trust ceases to be a grantor trust. The recaptured amount must be reported as gross income on the donor’s final income tax return. Reg. 1.170A-6(c)(4).

A grantor lead trust is usually funded by a high-income donor who could benefit from an immediate income-tax deduction. Such a donor may have had one single large income-generating event that will create a large tax bill in a year, which may be offset by the charitable deduction. Alternatively, the donor may presently be in a high-income tax bracket where the donor will benefit from a charitable deduction now, and anticipates being in a lower tax bracket in the future when the remaining assets will be transferred back to the donor or the donor’s estate. The distribution of the trust corpus to the grantor is not a taxable event because the tax implications are handled throughout the duration of the trust.

Non-Grantor Lead Trust

The non-grantor lead trust is often referred to as a family lead trust because the remainder passes from the trust to the grantor’s family members. The goal of a family lead trust is to generate a gift or estate tax deduction which allows assets to be passed to family or other beneficiaries at a reduced gift or estate tax cost. One of the greatest benefits of a family lead trust is that the charitable deduction generated by the gift may reduce future estate taxes.

A family lead trust is its own taxable entity and must file IRS Form 1041. This means that the trust itself pays taxes on all income generated, including capital gains income, in excess of the charitable payments. If the family lead trust is funded with appreciated property and that property is sold by the trust, the payment of capital gains tax could cause a significant reduction in trust corpus.

Unlike the grantor lead trust, there is no up-front income tax deduction for a family lead trust. The family lead trust generates an up-front gift tax deduction if it is an inter vivos trust or an estate tax deduction if it is a testamentary trust. In addition, the trust itself is able to deduct charitable payments made each year against income generated from the trust.

Example: Caroline plans to create a $15 million non-grantor charitable lead annuity trust (CLAT). The CLAT will have a fixed payout of $300,000 per year, a 20-year term and Caroline’s children will be the remainder beneficiaries. Caroline funds the trust with $15 million of stock.

If Caroline funds the lead trust with her stock, the annual annuity payment will consist of dividend income and realized capital gain, totaling $280,000. Because the trust will pay out $300,000 per year to charity, it will be able to deduct the entire $280,000 from its taxable income. The trustee may sell $20,000 of the stock each year to make up the difference to charity. The tax on the $20,000 is offset by the Sec. 642(c) charitable income tax deduction.

Lead Supertrust

The third type of lead trust is called a defective grantor lead trust by tax professionals. A better marketing term is a lead supertrust. The same rules generally apply as to a grantor lead trust, however instead of the trust assets reverting to the grantor at the end of the term, the remainder passes to the grantor’s family. Defective grantor lead trusts are sometimes called lead supertrusts because they achieve the goals of generating a current income tax deduction and a gift-tax deduction.

With a lead supertrust, the donor receives an up-front income and gift-tax deduction for the present value of the income projected to go to charity. The donor pays all taxes during the term of the trust for any taxable events that occur within the trust, in a manner similar to a standard grantor lead trust. However, instead of the trust corpus reverting to the grantor or the grantor’s estate at the end of the trust term, the remaining trust corpus will pass to the donor’s family. Additionally, the lead supertrust is not included in the grantor’s taxable estate.

In order to qualify as a lead supertrust, the trust must qualify as a grantor trust, which allows the income-tax deduction. But, unlike the requirements for a standard grantor lead trust, the trust must also qualify as a complete gift. The grantor must not retain certain powers over the trust, which will allow the trust to be excluded from the donor’s estate. The grantor must not retain a right of reversion of trust assets or the right to control the distribution of income. Sec. 2036(a). The preferred retained power to allow the trust to qualify as a grantor trust, but exclude the trust assets from the grantor’s estate is the power of a non-adverse party to reacquire trust assets. Sec. 675(4). A non-adverse party may be any party not subject to the self-dealing rules under Sec. 4941. While a grantor could argue that retaining and exercising such a power would be permitted under the “incidental exception” to the self-dealing rules (Reg.53.4941(b)-3), a more conservative option is often to give a sibling of the donor the power to reacquire the trust assets. The Sec. 4941 disqualified persons category includes spouses, children, grandchildren and their spouses, but not brothers or sisters, so this provision would not violate the self-dealing rules. Sec. 4946(d). The sibling would also need to be able to exercise this power in a non-fiduciary capacity to cause the lead trust to be a grantor trust. See PLR 200010036.

In the year when the assets are transferred to the trust, the donor will receive an income and gift tax deduction for the present value of the remainder interest to charity. The donor must file a Form 709 gift tax return. On the gift tax return the donor will report the trust value, the charitable gift deduction and the taxable transfer to the remainder beneficiary. The donor may use gift exemptions to cover the taxable transfers.

Example: John sold a commercial building this year that he inherited many years ago from his parents. He has a spike in his taxable income due to the sale and would like to generate a charitable deduction to offset some of the taxes. John would also like to provide a nice inheritance for his children, but he wants to give his children time to mature and make their own way before receiving a large lump sum.

John decides to transfer $3,000,000 to a 15-year lead supertrust. The present value of the annual 3% payout to charity is $1,350,000. Because his income is about $3,300,000 this year, John will be able to use $990,000 of the deduction this year under the 30 percent of adjusted gross income limit. He will carry forward the remaining $360,000 to use in the next year. He can carry forward his deduction for up to five years.

The trust remainder will be transferred to his children at the end of the trust duration. John does not retain control over the income or a reversion in the trust. He gives his sister, Rebecca, a Sec. 675(4) power to reacquire the trust assets, enabling the trust to qualify as a grantor trust. In the year the trust is funded, John must file a Form 709 gift tax return. He will report a charitable gift tax deduction of $1,287,342, which reduces the taxable transfer to his children from $3,000,000 to $1,712,658. He uses part of his unified estate and gift exemption ($10 million plus indexed increases) to cover the $1,712,658 gift.

Over the 15-year period of the trust, assuming the invested assets produce a total return of 6 percent, the trust will grow to over $5,000,000. John will benefit from a sizeable income tax deduction, receive a gift tax deduction and be able to transfer over $5,000,000 to his children. The $5,000,000 to the children will be tax-free upon receipt, as John has paid all taxes during the term of the trust. The combined benefits of the plan make this an effective planning strategy for John.

Due to the multiple ways to structure a lead trust, individuals with high net worth may find a charitable lead trust to be a good solution for estate, gift or income tax planning. The structure of the lead trust determines the unique income, estate or gift planning opportunities for the grantor of the trust. This article is Part I of a two-part series. Part II will discuss the unique planning opportunities currently available with CLTs with a focus on the historically low applicable federal rates (AFR).

Charitable Class and Disaster Relief

In order to qualify as a charity under IRS Code Sec. 501(c)(3) and obtain or maintain tax-exempt status, a non-profit organization must serve a "charitable class." In the wake of natural and man-made disasters, and now in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, many charities are created. In addition, existing charities are reaching out to serve those who are in need due to current events. However, charities need to ensure they are protecting their tax-exempt status by assisting an appropriate charitable class.

Nevertheless, guidance from the IRS is unclear as to what constitutes a charitable class. In many instances, guidance from IRS Regulations and individually issued Private Letter Rulings (PLRs) determine what does not qualify as a "charitable class," as opposed to a definition stated in the affirmative. This article discusses the historical requirement of a charitable class, specific IRS and Congressional guidance issued after September 11, 2001, the prohibition against private benefits and a different route for qualification for tax-exempt status based on the standard of "lessening the burdens of government."

Tax Code Charitable Class Requirement

To maintain tax-exempt status under Sec. 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), an organization must be organized and operated exclusively for exempt purposes set forth in Sec. 501(c)(3), and none of its earnings may inure to any private shareholder or individual. Exempt purposes are defined in Sec. 501(c)(3) as charitable, religious, educational, scientific, literary, testing for public safety, fostering national or international amateur sports competition, and preventing cruelty to children or animals. The IRC explains that "charitable" purpose is used in its generally accepted legal sense and includes relief of the poor and the distressed, or the underprivileged; and lessening the burdens of government. Reg. 1.501(c)(3)-1(d)(2).

However, the IRS acknowledges that these categories can and have changed over time since the regulations were issued in 1959. Additionally, the tax regulations do not specifically mention a charitable class. As scholars have noted, there is a lack of guidance on point regarding a charitable class and private benefits. Essentially, the IRS requires a charity to serve a charitable class without providing much guidance for charities on how to ensure compliance with the requirement.

According to IRS Publication 3833, "Disaster Relief: Providing Assistance Through Charitable Organizations," a charitable class is "a group of individuals that may properly receive assistance from a charitable organization. A charitable class must be either large enough that the potential beneficiaries cannot be individually identified, or sufficiently indefinite that the community as a whole, rather than a pre-selected group of people, benefits when a charity provides assistance."

While potentially helpful in deciphering the definition of a charitable class, it is important to note that IRS publications are not authoritative, but merely instructive. The IRS holds, and a line of court cases agree, that the authoritative tax law is embodied only in official statutes, regulations and judicial decisions. Unraveling IRS requirements can leave charities in a dilemma when trying to assist individuals in need, especially when the need is due to a disaster that requires swift assistance.

IRS and Congressional Guidance After September 11

The IRS and Congress have set forth parameters on the topic of charitable classes in the past. Following the events of September 11, 2001 (9/11), the IRS issued Notice 2001-78, 2001-2 C.B. 576 to clarify disaster relief requirements for charities attempting to assist 9/11 victims and first responders. The Notice stated, "While Congress is considering legislation, the Service recognizes the need to provide interim guidance to charities regarding payments made by reason of the death, injury or wounding of an individual incurred as a result of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks against the United States."

In terms of a charitable class, the Notice provided "the Service will treat such payments made by a charity to individuals and their families as related to the charity's exempt purpose provided that the payments are made in good faith using objective standards." This guidance allowed charities to react quickly to the communities that needed assistance the most. Charities were able to mobilize using good faith, objective standards.

After the Notice's release, Congress enacted the Victims of Terrorism Tax Relief Act of 2001 (VTTRA). The VTTRA allowed charitable payments made by charities assisting those affected by 9/11 to "be treated as related to the purpose or function constituting the basis for such organization's exemption under Section 501 of such Code if such payments are made in good faith using a reasonable and objective formula which is consistently applied." This legislation statutorily solidified the IRS' earlier guidance for charities.

However, this legislation and IRS guidance are only applicable for charitable distributions made in response to 9/11 and the following anthrax attacks. Therefore, charities attempting to assist those in need due to other disasters, including the current pandemic, may not be able to use the "good faith objective" standard. Charities must instead follow the general standards set forth in the tax code.

Providing a Private Benefit

Congress has established through regulations (and the IRS has provided examples within regulations and PLRs, which are only binding on the parties seeking a ruling, but can be used to provide insight into IRS decision-making) that charities providing a "private benefit" risk their tax-exempt status. An organization is "not organized or operated [for a charitable purpose] unless it serves a public rather than a private interest. Thus…it is necessary for an organization to establish that it is not organized or operated for the benefit of private interests, such as designated individuals, the creator or his family, shareholders of the organization, or persons controlled, directly or indirectly, by such private interests." Reg. 1.501(c)(3)-1(d)(ii).

The requirement to provide a public rather than a private benefit is meant to serve a charitable class with a large group of potential beneficiaries, or the community as a whole, rather than a pre-selected group of people. However, the IRS does not always directly connect the charitable class requirement to the prohibition against private benefit.

Public Rather than Private Benefit

Scholarships are frequently an issue the Service examines to ensure there is not a private benefit conferred upon an individual. In Reg.1.501(c)(3)-1(d)(iii), the Service provides the example of an educational organization whose purpose was to study history and immigration. However, the focus of the organization's study in history was the genealogy of one family. The organization solicited membership only for members of that one family and the organization performed research to locate members of that family and connect them with one another. The Service notes that the interests in a case like this primarily serve a private rather than a public interest. Therefore, tax-exempt status for this organization would be denied. While an organization may potentially have a large charitable class, if the facts and circumstances demonstrate that a private benefit rather than a public interest is being served, tax-exempt status may be jeopardized.

Indefinite Rather than Preselected Beneficiaries

Common law recognizes the need for a charitable class to include a group of indefinite beneficiaries. This means that charities set up for the public benefit - and therefore qualifying for tax exemption - must aid an indefinite number of people who cannot be particularly identified. However, this common law understanding has not been defined or codified by the IRS or Congress in any official documents. The absence of a large, indefinite class of beneficiaries may then cause problems for organizations attempting to assist a small, but potentially deserving group of people.

The case of Wendy L. Parker Rehabilitation Foundation Inc. v. Commissioner examines private benefit, but has also been cited in later cases as providing a benefit to a particularly identified individual. In Wendy L. Parker, the Tax Court examined private benefit in relation to a purportedly indefinite charitable class. The family of Wendy Parker, a coma victim, established a foundation to assist coma victims. However, 30% of the foundation's income was anticipated to be spent assisting Parker. The foundation was denied tax-exempt status because "a child of the founder and chief operating officer of the Foundation is a substantial beneficiary of the services contemplated by the organization. This constitutes inurement which is prohibited under Code Section 501(c)(3) and the Regulations there under."

While the class of individuals was indefinite, the anticipated private benefit to Parker defeated the request for exempt status. The Tax Court noted "the 'operated exclusively for exempt purposes' test and the 'private inurement' test are separate requirements, although there is substantial overlap." While the result may have been different with the exclusion of the private inurement to a disqualified person, the Service has also noted in other cases citing Wendy L. Parker that the services of a charity must not be provided for a preselected individual.

In PLR 201923026, the IRS cited Wendy L. Parker in denying an exemption to an organization formed to host a fundraiser for five orphaned siblings whose parents died within a year of each other under tragic circumstances. The fundraiser was to help offset the children's living expenses. The IRS held that the fundraiser was operated for the "private benefit of one family rather than operating to provide a public benefit. Despite the fact that funds are raised and expensed for orphaned children the beneficiaries are pre-selected and all from one family. This serves private rather than public interests."

The Service directly compared the case to Wendy L. Parker and stated, "You have set up a process whereby pre-named beneficiaries are able to collect funding. Regardless of whether the…children are related to any board members, or meet the definition of needy, they have been predetermined to receive your funding without documented cause, making them a direct beneficiary and recipient of your income, resulting in inurement."

Although the children were not disqualified persons to the organization, the Service held that the class of beneficiaries was too small and predetermined to receive aid to qualify. The results in Wendy L. Parker and PLR 201923026 are instructive as scenarios charities should avoid. Educational institutions often provide support to what may be a small class of individuals in the form of grants and scholarships, but the recipients are not typically pre-selected. When educational scholarship recipients are chosen, it is required that the recipients are selected based on objective qualifications with the goal of avoiding private benefit.

Determination of Need on an Individual Basis

In PLR 201509039, the IRS denied tax-exempt status to a nonprofit organization that was created to offer funds to small businesses in areas affected by natural or man-made disasters. The organization's purpose was to assist small businesses impacted by disasters by connecting them with consumers so that the business would be able to avoid closure and employee layoffs. According to the PLR, "In order for an organization to fulfill a charitable purpose, it generally must assist a charitable class of individuals. If an organization allows its activities to benefit individuals beyond a charitable class, then it is not a charitable organization. See Wendy Parker Rehabilitation Foundation, Inc. v. Commissioner. Small businesses in areas affected by a disaster are not a charitable class, per se. Some of these businesses may have large sums of cash in reserve." Therefore, the Service ruled that because the organization did not make a determination of need on an individual basis, the organization did not qualify for exempt status.

However, the requirement to determine individualized need is often burdensome for charities, especially those wishing to offer expedient assistance after disasters. For charities to assist those in need due to disasters, IRS guidance would require charities to perform an assessment to discover the individual needs of recipients. Many organizations are not equipped to determine individualized needs, especially when time may be of the essence in providing assistance.

IRS guidance in the past has focused on individualized needs because "maintaining a person's standard of living at a level satisfactory to that person rather than at a level to satisfy basic needs would overly serve private interests" and "an outright transfer of funds based solely on an individual's involvement in a disaster without regard to meeting that individual's involvement in a disaster or without regard to meeting that individual's particular distress or financial needs would result in excessive private benefit." IRS Disaster Relief Guidance Memorandum, in response to Oklahoma City Bombing, Aug.25, 1995.

This particularized determination of need can be difficult for charities to make, especially in the wake of disaster when quick action is necessary. After the Boston Marathon Bombing in 2013, One Fund Boston was established to assist those affected by the tragedy. The Fund distributed over $80 million received in donations to survivors and families on a "need-blind basis."

The One Fund team created a strategy, working with the mayor and the City of Boston to meet the criteria for tax-exempt status based on "lessening the burdens of government." This strategy is one method of qualifying as a Sec. 501(c)(3) organization where the IRS does not examine the extent of the charitable class. Instead, the IRS will seek to determine if 1) there is a certain activity the government considers to be its burden and 2) if the activity lessens the government's burden.

While this method was successful for this instance, it should be used with caution. This method has not been tested extensively in the area of disaster relief. Charities should seek further guidance from their counsel to determine if this route is appropriate.

Conclusion

Unless and until more guidance in the form of regulations and statutes is released, charities will need to continue to abide by current IRS rules. In order to follow the limited guidance related to charitable class, charities must avoid providing a private benefit and must seek to establish an individualized determination of need, otherwise their tax-exempt status may be compromised. The rules promulgated after the 9/11 attack through the VTTRA only applied for that particular disaster. For COVID-19 or other disaster situations, charities must look to general IRS requirements for guidance or request that Congress pass laws, as it did after 9/11, to provide clear instructions for charitable distributions.

Protection From Covid-19 Scams

As part of the Security Summit, the Internal Revenue Service published a guide on how to protect yourself from phishing scams. The new scams attempt to prey on taxpayers and tax advisors using COVID-19, Economic Impact Payments, and taking advantage of teleworking by tax professionals.

IRS Commissioner Chuck Rettig stated, "The coronavirus has created new opportunities for cybercriminals to use email to try stealing sensitive information. The vast majority of data thefts start with a phishing email trick. Identity thieves pose as trusted sources – a client, your software provider or even the IRS – to lure you into clicking on a link or attachment. Remember, don't take the bait. Learn to recognize and avoid phishing scams."

The Security Summit emphasized four general phishing strategies. These include an urgent message, a delayed notice, COVID–19 fears, and posing as a client.

1. Urgent message

A common phishing scam is to send a message that appears to be urgent. It may claim to be from one of the victims' financial institutions and explains that an account password or log in information has expired. The victim is directed to click on the link to restore account data. The phishing email often comes from a site that is one letter or number different from the official website. When the user clicks on the link, malware is installed on the computer, which enables the thief to steal personal information and passwords.

2. Delayed notice

After the thief has installed malware on a computer, he or she may delay taking action for a period of time. One tax preparation firm had thieves on their network for 18 months without any indication. The thieves downloaded and accessed taxpayer information during that entire timeframe prior to the discovery of the information technology breach.

3. COVID–19 Fears

Another common phishing attack is for the fraudster to claim to be a provider of face masks or personal protective equipment (PPE). The scammer explains that the face masks or PPE are in such short supply that you need to order immediately from his or her organization. When you click to order, the scammer loads malware on your computer.

4. Posing as a client

Many tax professionals are in daily communication with large numbers of existing clients. A fraudster may hack the email account of a client and then send an email to the tax professional. The tax professional may be expecting contact from that client and does not realize that the email has been sent from a different web site or server. When the tax professional clicks on a link, malware is downloaded. Tax professionals are urged by the Security Summit to make contact with clients by phone or video conference if they receive a suspicious email.

Everyone needs to be aware of the risk of phishing emails. Most successful fraudster attacks start with a phishing email. Tax professionals must continually educate their staff on the "dangers and risks of opening suspicious emails – especially during the COVID-19 period."

Additional security recommendations are available in IRS Publication 4557, Safeguarding Taxpayer Data and in the Small Business Information Security: The Fundamentals by the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Final Regulations on Salt Charitable Workarounds

On August 10, 2020, Treasury published final regulations (T.D. 9907) on the state and local tax (SALT) workarounds involving charitable gifts and state tax credits.

New York, Connecticut, New Jersey, and other states were concerned about the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act $10,000 limit on SALT deductions. They created several "workaround" programs that would allow individuals to make charitable gifts to government entities and report the charitable deduction on their federal tax return. The State then granted the individual a reduction in state taxes through a credit.

Charitable contributions are generally deductible under Sec. 170(a)(1). This deduction is permitted for gifts to a nonprofit or a governmental entity such as a state or a political subdivision of a state.

Business entities are permitted a deduction for ordinary and necessary expenses under Sec. 162(a). Regulation 1.162–15(a) limits business ordinary and necessary deductions if there has been a deduction under Section 170 or another code provision.

Section 164(a) permits deductions for state and local taxes. Section 164(b)(6) limits the SALT deduction to $10,000 per year.

To limit the use of a charitable workaround to provide SALT deductions in excess of $10,000, in 2019 Treasury published final regulations on the topic. The final regulations state, "If a taxpayer makes a payment, or transfers property to or for the use of an entity described in Section 170(c), and the taxpayer receives or expects to receive a State or local tax credit in return for such transfer, the tax credit constitutes a return benefit to the taxpayer, or quid pro quo, reducing the taxpayer's charitable contribution deduction." Reg. 1.170A–1(h)(3).

Businesses were concerned that the anti–SALT regulations would limit their ordinary and necessary expense deductions under Sec. 162. The IRS final regulations are designed to clarify the deductibility of transfers by business entities. The final regulations state, "A transfer to a Section 170(c) entity may constitute an allowable deduction as a trade or business expense under Section 162, rather than a charitable contribution under Section 170."

The final regulations also provide safe harbors for a C corporation or pass-through entity to qualify for a deduction under the ordinary and necessary business expense standard of Sec. 162. The safe harbors apply only to gifts of cash and cash equivalents. For some passthrough entities, the safe harbor does not apply if there is a state or local income tax credit.

The final regulations retain the Sec. 164 safe harbor. If a portion of a contribution is disallowed under Reg. 1.170A–1(h)(3), it is still deductible under Sec. 164, provided it is not excluded by the $10,000 tax limitation under Sec. 164(a)(6).

Finally, the regulations apply the quid pro quo rule to cover donors who receive benefits either from a donee or a third party. The final regulations "amend the language in Reg. 1.170A–1(h)(2)(I)(B) to state that the fair market value of goods and services includes the value of goods and services provided by parties other than the donee."

Editor's Note: The regulations are generally effective August 11, 2020. These regulations are consistent with efforts by Treasury to limit the effectiveness of the SALT workarounds, while continuing to permit businesses to deduct ordinary and necessary expenses.